A virulent stream of hyper-partisan political conflict that spilled over into the nation’s public schools in the past two years has had a chilling effect on high school education.

Many educators have sought to avoid controversy by pulling back on teaching lessons in civics, politics, and the history and experiences of America’s minority communities, among other topics now deemed to be too controversial for the classroom. Many teachers and administrators are considering leaving the profession. And incidents of verbal harassment of LGBTQ students are on the rise.

Such are some of the findings of a new report by UCLA and UC Riverside education professors John Rogers and Joseph Kahne entitled “Educating for a Diverse Democracy: The Chilling Role of Political Conflict in Blue, Purple, and Red Communities," published Nov. 30 by UCLA’s Institute for Democracy, Education and Access.

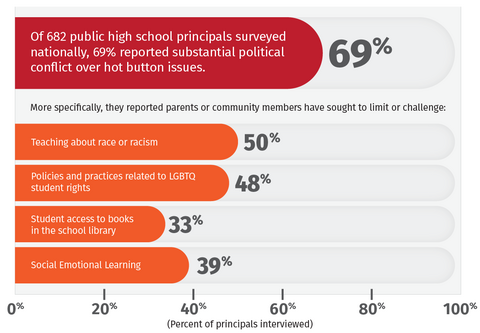

More than two-thirds of the 682 high school principals across the nation interviewed for the report said heated political conflicts are impacting their schools, with the highest levels of strife in schools that are within politically divided “purple” congressional districts. Highly vocal parents, often misinformed, are increasingly challenging instruction about race and racism, policies and practices concerning LGBTQ rights, access to books in the school library, and social-emotional learning methods, the report found.

Many schools have responded by avoiding the subjects now deemed controversial. These topics include lessons about our nation’s eras of slavery and Jim Crow segregation and works of literature about race or by minority writers. Even social studies lessons covering the basics about how our government and democracy functions and teaching students how to discern accurate information from disinformation have become, in some communities, too hot to handle.

The chilling effect of these controversies erodes the essential role public schools play in a functioning democracy that encourages participation among all cultural and ethnic groups of citizens, Kahne said.

Ideally, schools provide a foundation of diverse democracy by fostering respectful discussions of controversial topics. That includes teaching students to form opinions based on accurate information and thoughtful consideration; teaching the stories, histories, and current realities of the of people who make up the democracy and, finally, respecting the humanity and dignity of all people, Kahne said. The principals reported behaviors that threaten democracy, Kahne said. Throughout the country, people who don’t have children in the schools, many acting under the guidance of conservative national political or interest groups, attended school board meetings and distributed misinformation and refused to acknowledge accurate information, he said.“I'm not talking about parents voicing their opinions. Hostile and threatening statements are being made ...,” Kahne said. “Those sorts of dynamics actually make it harder for schools to do what they need to do to prepare young people.”

Consider the experience of a principal in Minnesota interviewed for the report.

“I value diversity and teaching [and] learning about diversity...,” the principal said. “I thought I could at least start to touch on it because it's a very white community and their students of color struggle a lot.

“My superintendent told me in no uncertain terms that I could not address issues of race and bias, etc., with students or staff this year ... He told me, ‘This is not the time or the place to do this here. You have to remember you are in the heart of Trump country and you're just going to start a big mess if you start talking about that stuff.’” The report kept the names of the principals confidential.

Until recently, school board meetings have been mostly dull, sparsely attended affairs, Kahne said. A shift occurred, however, following the election of Donald Trump as president, which coincided with a decline in trust in government and civility in public discourse. After the COVID-19 pandemic began, school board meetings became focal points of passionate debate about if, when, and how schools would reopen. Then came cultural war attacks on curriculums that covered racial histories and experiences, policies related to LGBTQ student rights, and access to certain library books.

In many communities, vocal citizen groups have accused schools of teaching “critical race theory” or CRT. when the schools provided instruction about pre-Civil War slavery, the civil rights movement, or about works of literature or film that address racial issues.

An Ohio principal, for example, said parents launched an investigation into the school's curriculum using an anti-CRT playbook created by conservative activist Christopher Rufo. When no evidence was found, the group claimed the school was teaching “undercover CRT” and they demanded that Toni Morrison’s first novel, “The Bluest Eye,” which tells the story of an African America girl growing up in an Ohio town just after the Great Depression, be removed from classrooms and the school library.

Similarly, an Iowa principal said parents asked the school to remove books that explore issues of race, including the Harper Lee classic “To Kill a Mockingbird.” They also complained when a teacher showed clips from the biographical drama “Hidden Figures,” which highlights the contributions of African American women to NASA’s early spaceflight.

Fallout goes beyond topics deemed controversial. The principals reported the conflicts have left many principals and teachers considering retirement or career changes. Another finding was that schools in the most contentious purple and red communities were the least likely to offer teachers the professional development training and resources needed to better teach about controversial topics.

The conflict was not limited to school board meetings. Compared to a similar survey completed in 2018, the principals reported an increase in the number of students making hostile or demeaning remarks to their LGBTQ classmates. In purple communities, the percentage of principals reporting such remarks jumped from 10 percent to 32 percent.

A Massachusetts principal said, “The past two years have been the hardest years of my career and they have left me worried about the future of public education ... This is an existential moment for the cause of public schools in this country.”

Fortunately, Kahne and his UCLA colleague, Professor John Rogers, identified two factors that were strongly associated with education for a diverse democracy.

Schools run by principals who were civically engaged and schools where district leadership emphasized the importance of civic education were far more likely to support education for a diverse democracy, Kahne said. In short, the report found, school and district leadership can make a big difference — and importantly, these factors made a big difference in blue, purple and red communities.

Original source can be found here

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up